Ever since I published my memoir, Daughter of Spies, Wartime Secrets, Family Lies which focuses on my mother, readers have asked me if I’m going to write a book about my father.

“No,” I reply.

“Why not?”

I have more than one answer to that question.

The first is that my father, Stewart Alsop, wrote his own memoir, Stay of Execution, about being told he was going to die of leukemia in a pretty short time.

(The doctors originally told him six weeks, but he lasted almost three years beyond that first dire prognosis.) In the book, he looks back over his life while describing the ups and downs of blood scans, bone marrow tests and early forms of immunotherapy. His braided narrative inspired my own when it came to writing about losing my mother to dementia while trying to get down the stories of her childhood in Gibraltar, her life in the war as a decoding agent, and her marriage to an American soldier who’d enlisted in the British Army.

I always remind the questioner that in addition to his own memoir, many books have been written about the Alsops, my journalist father, Stewart, and his older brother, Joseph, not to mention a play based loosely on their lives that opened on Broadway with John Lithgow playing my uncle. But the final, real answer is that I believe readers want most of all to understand my father’s political history as a Washington based reporter from 1946 until his death in 1974 at the age of 60. And that’s a history that’s been analyzed and described and dissected by the writers who wrote the books mentioned above… and simply put, it’s one that, as a fiction and memoir writer, not a political historian, I don’t need to try to re-examine.

However, there are stories about my father that I learned while doing the research for Daughter of Spies that I chose not to include because I had been cautioned by the astute editor, William Zinsser, that you can only write about one parent at a time and I chose my mother.

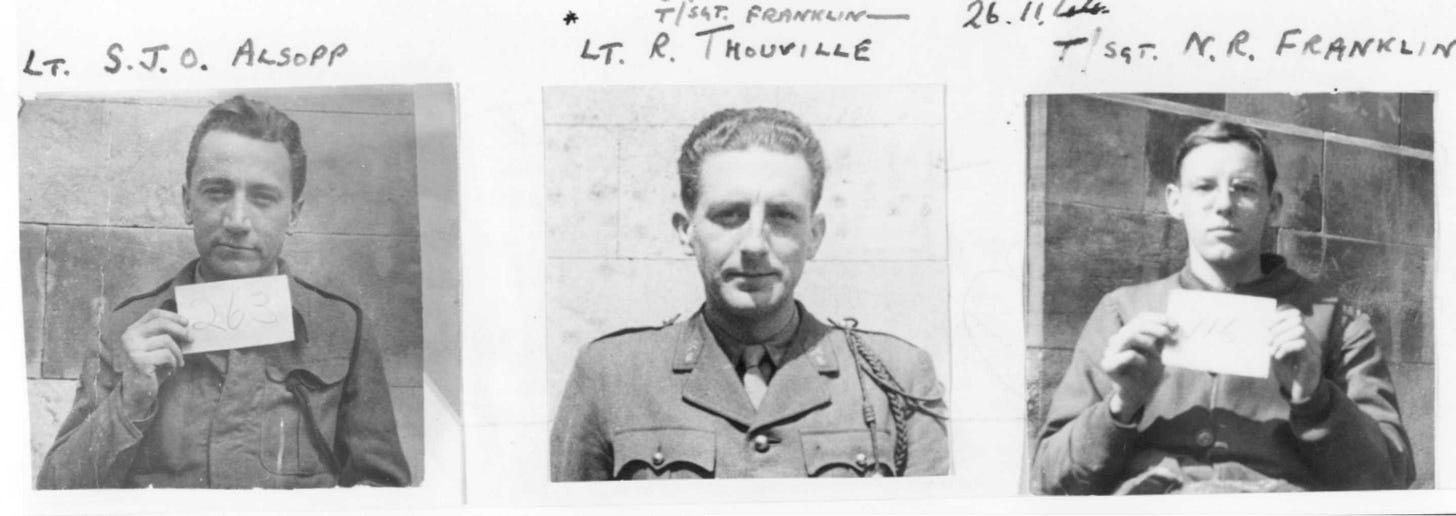

One story from the war was told to me by a fellow named Dick Franklin, the radio operator who parachuted with my father behind enemy lines into France in the summer of 1944. Dick was 18 that year and my father, the captain of Team Alexander, was 30. The third member of the team was a Frenchman who used an alias as he’d already escaped from a prisoner of war camp.

As children, we heard the funny stories about their time in France from the raucous parties in chateaux abandoned by the fleeing Germans or the time Daddy jumped out of the plane too early and floated down through moonlit skies with every dog in France barking at his imminent arrival.

One story my father didn’t tell us was a small one, but I treasure it as it says a lot about the kind of captain he was. Team Alexander landed in France August 13, 1944 and were hidden by members of the Maquis (French Resistance) in a farmhouse. The next morning, a lady brought them two flags, one American, one French, fashioned during the night from the men’s parachutes, and more importantly, three bicycles. The team pedaled miles away from the farmhouse so that Dick could set up the radio equipment and make their first contact with London. To his horror, Dick discovered that he’d left behind the crystals, a crucial component for the transmission. Years later he wrote about the incident in his memoir.

“Without a word, Alsop jumped on his bike and rode back to the farm. Fortunately, he was able to find the crystals and return in time for the sked. I should have expected a good chewing out. He never mentioned the incident, at least not to me.”

Or to us children.

My father would have been 111 years old in May. In these times, when we are searching for true patriots and resistance fighters, I decided to focus on him because he was both.

What an extraordinary life!! Best, Steve S.

Pamela, so glad you have found me. And you certainly describe Uncle Joe well. He had a big heart and an even bigger personality.