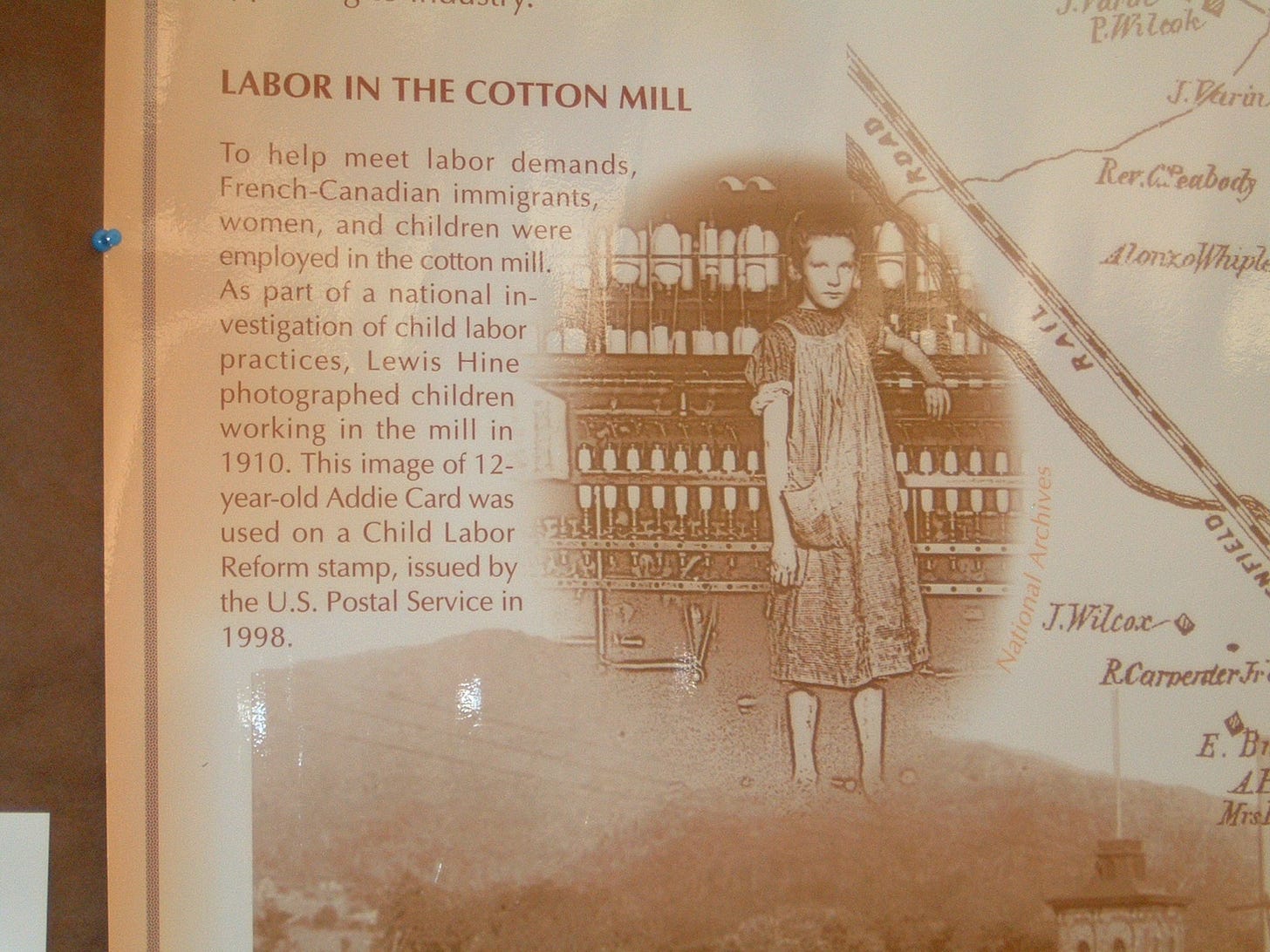

In 2007, I published Counting on Grace, a work of historical fiction that told the story of a 12-year-old mill worker, a girl who “doffed” the bobbins in a textile mill in North Pownal, Vermont. My character was inspired by this photograph of a textile worker, taken by Lewis Hine, the photographer who traveled all over America documenting

the lives of children who worked long days in dangerous industries like coal mining, oyster shucking, glass blowing and textile factories to name a few. When I first saw the photograph in a Vermont museum, I didn’t want to know anything about the actual child in the picture. I simply used her weary face, her filthy smock and her dirty bare feet as an inspiration for my story.

But once the novel had moved to the copyediting stage, I began to wonder about the actual child, the one who inspired my story. Hine had listed her as Annie Laird, but when we couldn’t find an entry for a child by that name in the 1900 census, I realized that Hine probably couldn’t hear what she told him over the noise of the spinning frames. So with a bit of imagination, the help of a local genealogist/researcher and some deeper digging, we found Addie Card and her older sister, Annie in that census.

In the end, with the help of her descendants, we pieced together Addie’s story. She married a fellow mill worker, had a child, divorced and ended up living across the border in New York State. She died at the age of 93, never knowing that her face appeared in a Reebok ad decrying child labor or on a 1998 postage stamp.

I made sure that the billboard on the former site of the mill in North Pownal listed her correct name as did the entry in the Library of Congress Hine collection.

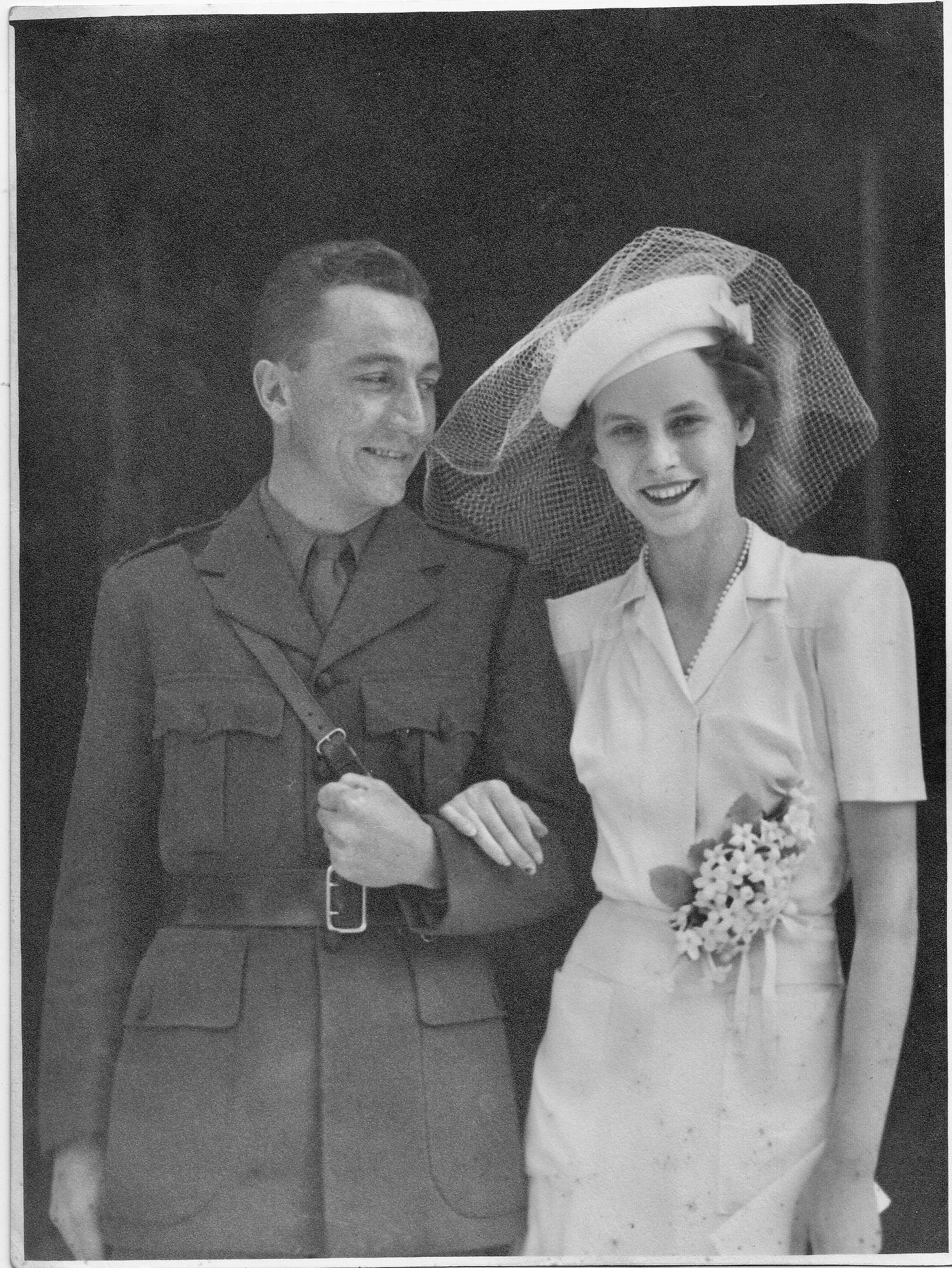

A writer coming off a book can get distracted by the marketing and publicity work, but I’ve always maintained that even then, a writer is never not writing. So, when I found myself at the end of the story of Grace, I suddenly realized that I knew more about Addie Card than I did about my own mother. Without knowing where my research would lead me, I turned my attention to my Gibraltar-born mother, her childhood by the Mediterranean and in England, her life in London during the war and her marriage to my father, a Yank who enlisted in the British Army.

Books start long before the writer knows what she’s doing or where she’s going. I thought I was simply filling in the gaps in my mother’s story. She’d always kept her counsel and had seemed content to let my father’s big noisy American family garner all the attention. But as I began to learn more about her, I could feel a book taking shape, this time a memoir that would start with my mother’s peculiar childhood in Gibraltar and my parents’ wartime romance and go on to tell the story of my childhood in cold war Washington, where we were surrounded by famous politicians, diplomats and CIA operatives.

The problem was I’d never written a memoir before, so I had to learn a new way of using the tools of fiction. It took me longer than usual to find my voice in this book, to discover the difference between autobiography and memoir and to find a way to tell my mother’s story without letting hers overshadow mine. In Daughter of Spies: Wartime Secrets, Family Lies I learned to use a braided narrative, one that moves back and forth from the past to the present. Memoir requires structure but like most projects, including novels, the book teaches the writer what it’s about while she’s writing it.

And it’s only in looking back that I realize the exploration of my mother’s story began with a search for a little girl in Vermont whose photograph had become iconic but whose story had been tossed into the dustbin of history.

Great piece Elizabeth!